Letters Made Out of Objects Layered Over and Over Again

In textual studies, a palimpsest () is a manuscript folio, either from a scroll or a book, from which the text has been scraped or washed off then that the page tin can be reused for another document.[1] Parchment was made of lamb, calf, or goat kid peel and was expensive and not readily bachelor, so in the interest of economy a page was oftentimes re-used by scraping off the previous writing. In vernacular usage, the term palimpsest is too used in architecture, archaeology and geomorphology to announce an object fabricated or worked upon for i purpose and later reused for another, for instance a monumental brass the contrary blank side of which has been re-engraved.

Etymology [edit]

The word palimpsest derives from the Latin palimpsestus, which derives from the Ancient Greek παλίμψηστος[2] ( palímpsēstos , from παλίν + ψαω = 'once more' + 'scrape'), a compound word that describes the process: "The original writing was scraped and washed off, the surface resmoothed, and the new literary cloth written on the salvaged material."[iii] The Ancient Greeks used wax-coated tablets, like scratch-pads, to write on with a stylus, and to erase the writing by smoothing the wax surface and writing again. This practice was adopted by Aboriginal Romans, who wrote (literally scratched on letters) on wax-coated tablets, which were reusable; Cicero's use of the term palimpsest confirms such a practise.

Evolution [edit]

A Georgian palimpsest from the 5th or sixth century

Because parchment prepared from animal hides is far more durable than paper or papyrus, virtually palimpsests known to modern scholars are parchment, which rose in popularity in Western Europe after the 6th century. Where papyrus was in common employ, reuse of writing media was less common because papyrus was cheaper and more expendable than plush parchment. Some papyrus palimpsests do survive, and Romans referred to this custom of washing papyrus.[note 1]

The writing was washed from parchment or vellum using milk and oat bran. With the passing of time, the faint remains of the former writing would reappear plenty then that scholars tin can discern the text (called the scriptio junior , the 'underwriting') and decipher it. In the after Centre Ages the surface of the vellum was usually scraped away with powdered pumice, irretrievably losing the writing, hence the near valuable palimpsests are those that were overwritten in the early Centre Ages.

Medieval codices are constructed in "gathers" which are folded (compare page, 'leaf, page' ablative instance of Latin folium ), and so stacked together like a paper and sewn together at the fold. Prepared parchment sheets retained their original cardinal fold, and then each was normally cutting in half, making a quarto volume of the original folio, with the overwritten text running perpendicular to the effaced text.

Modern decipherment [edit]

Faint legible remains were read by eye before 20th-century techniques helped make lost texts readable. To read palimpsests, scholars of the 19th century used chemical means that were sometimes very subversive, using tincture of gall or, later, ammonium bisulfate. Modern methods of reading palimpsests using ultraviolet calorie-free and photography are less dissentious.

Innovative digitized images assistance scholars in deciphering unreadable palimpsests. Superexposed photographs exposed in various light spectra, a technique called "multispectral filming", can increase the contrast of faded ink on parchment that is as well indistinct to be read by eye in normal light. For example, multispectral imaging undertaken by researchers at the Rochester Institute of Technology and Johns Hopkins University recovered much of the undertext (estimated to be more 80%) from the Archimedes Palimpsest. At the Walters Art Museum where the palimpsest is now conserved, the project has focused on experimental techniques to recall the remaining text, some of which was obscured by overpainted icons. 1 of the most successful techniques for reading through the paint proved to be Ten-ray fluorescence imaging, through which the iron in the ink is revealed. A team of imaging scientists and scholars from the United States and Europe is currently using spectral imaging techniques developed for imaging the Archimedes Palimpsest to study more than one hundred palimpsests in the library of Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula in Arab republic of egypt.[4]

Recovery [edit]

A number of ancient works have survived only every bit palimpsests.[note ii] Vellum manuscripts were over-written on purpose mostly due to the famine or cost of the fabric. In the example of Greek manuscripts, the consumption of old codices for the sake of the fabric was so great that a synodal decree of the year 691 forbade the devastation of manuscripts of the Scriptures or the church building fathers, except for imperfect or injured volumes. Such a decree put added pressure on retrieving the vellum on which secular manuscripts were written. The decline of the vellum trade with the introduction of paper exacerbated the scarcity, increasing pressure to reuse material.

Texts almost susceptible to being overwritten included obsolete legal and liturgical ones, sometimes of intense interest to the historian. Early Latin translations of Scripture were rendered obsolete by Jerome's Vulgate. Texts might exist in strange languages or written in unfamiliar scripts that had become illegible over time. The codices themselves might exist already damaged or incomplete. Heretical texts were unsafe to harbor—in that location were compelling political and religious reasons to destroy texts viewed as heresy, and to reuse the media was less wasteful than simply to fire the books.

Vast destruction of the broad quartos of the early on centuries took place in the period which followed the fall of the Western Roman Empire, but palimpsests were likewise created as new texts were required during the Carolingian Renaissance. The about valuable Latin palimpsests are found in the codices which were remade from the early large folios in the 7th to the 9th centuries. It has been noticed that no unabridged work is generally establish in any instance in the original text of a palimpsest, but that portions of many works have been taken to brand upward a unmarried book. An exception is the Archimedes Palimpsest (run into below). On the whole, early on medieval scribes were thus not indiscriminate in supplying themselves with material from any old volumes that happened to be at hand.

Famous examples [edit]

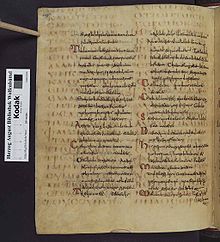

Codex Nitriensis, with Syriac text (upper text)

- The best-known palimpsest in the legal globe was discovered in 1816 past Niebuhr and Savigny in the library of Verona cathedral. Underneath letters by St. Jerome and Gennadius was the almost complete text of the Institutes of Gaius, probably the first students' textbook on Roman constabulary.[5]

- The Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris: portions of the One-time and New Testaments in Greek, attributed to the fifth century, are covered with works of Ephraem the Syrian in a mitt of the twelfth century.

- The Sana'a palimpsest is one of the oldest Qur'anic manuscripts in being. Carbon dating of the parchment assigns a appointment somewhere earlier 671 with a probability of 99%. Given that sūra ix, one of the final revealed chapters, is present and assuming the probable possibility that the undertext (the scriptio junior ) was written shortly later the preparation of the parchment, it was probably written relatively shortly, x to 40 years, after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The undertext differs from the standard Qur'anic text and is therefore the most important documentary testify for the existence of variant Qur'anic readings.[vi]

- Among the Syriac manuscripts obtained from the Nitrian desert in Egypt, British Museum, London: important Greek texts, Add. Ms. 17212 with Syriac translation of St. Chrysostom's Homilies, of the 9th/tenth century, covers a Latin grammatical treatise from the sixth century.

- Codex Nitriensis, a book containing a work of Severus of Antioch of the get-go of the 9th century, is written on palimpsest leaves taken from 6th-century manuscripts of the Iliad and the Gospel of Luke, both of the 6th century, and the Euclid'due south Elements of the 7th or 8th century, British Museum.

- A double palimpsest, in which a text of St. John Chrysostom, in Syriac, of the 9th or 10th century, covers a Latin grammatical treatise in a cursive manus of the sixth century, which in its plough covers the Latin annals of the historian Granius Licinianus, of the fifth century, British Museum.

- The only known hyper-palimpsest: the Novgorod Codex, where potentially hundreds of texts have left their traces on the wooden back wall of a wax tablet.

- The Ambrosian Plautus, in rustic capitals, of the fourth or fifth century, re-written with portions of the Bible in the 9th century, Ambrosian Library.

- Cicero, De re publica in uncials, of the 4th century, the sole surviving copy, covered past St. Augustine on the Psalms, of the 7th century, Vatican Library.

- Seneca, On the Maintenance of Friendship, the sole surviving fragment, overwritten by a late-sixth-century Old Testament.

- The Codex Theodosianus of Turin, of the fifth or 6th century.

- The Fasti Consulares of Verona, of 486.

- The Arian fragment of the Vatican, of the 5th century.

- The letters of Cornelius Fronto, overwritten by the Acts of the Council of Chalcedon.

- The Archimedes Palimpsest, a work of the peachy Syracusan mathematician copied onto parchment in the 10th century and overwritten by a liturgical text in the 12th century.

- The Sinaitic Palimpsest, the oldest Syriac copy of the gospels, from the 4th century.

- The unique copy of a Greek grammatical text composed by Herodian for the emperor Marcus Aurelius in the 2nd century, preserved in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek , Vienna.

- Codex Zacynthius – Greek palimpsest fragments of the gospel of Saint Luke, obtained in the island of Zante, by Full general Colin Macaulay, deciphered, transcribed and edited past Tregelles in 1861.

- The Codex Dublinensis (Codex Z) of St. Matthew'due south Gospel, at Trinity College Dublin, also deciphered past Tregelles in 1853.

- The Codex Guelferbytanus 64 Weissenburgensis, with text of Origins of Isidore, partly palimpsest, with texts of before codices Guelferbytanus A, Guelferbytanus B, Codex Carolinus, and several other texts Greek and Latin.

About sixty palimpsest manuscripts of the Greek New Testament have survived to the present day. Uncial codices include:

Porphyrianus, Vaticanus 2061 (double palimpsest), Uncial 064, 065, 066, 067, 068 (double palimpsest), 072, 078, 079, 086, 088, 093, 094, 096, 097, 098, 0103, 0104, 0116, 0120, 0130, 0132, 0133, 0135, 0208, 0209.

Lectionaries include:

- Lectionary 226, ℓ 1637.cvd

See also [edit]

- Palimpsest (disambiguation) for other uses of the word

- Pentimento

- Petroglyphs of Arpa-Uzen – rock art from the Bronze and Iron Ages after covered by Saka pictorials

Notes [edit]

- ^ According to Suetonius, Augustus, "though he began a tragedy with neat zest, becoming dissatisfied with the mode, he obliterated the whole; and his friends saying to him, What is your Ajax doing? He answered, My Ajax met with a sponge." (Augustus, 85). Cf. a letter of the hereafter emperor Marcus Aurelius to his friend and instructor Fronto (ad M. Caesarem, 4.5), in which the former, dissatisfied with a piece of his own writing, facetiously exclaims that he will "consecrate it to h2o (lymphis) or burn down (Volcano)," i.e. that he will rub out or burn what he has written.

- ^ The nigh accessible overviews of the transmission of texts through the cultural bottleneck are Leighton D. Reynolds (editor), in Texts and Transmission: A Survey of the Latin Classics, where the texts that survived, fortuitously, merely in palimpsest may be enumerated, and in his general introduction to textual transmission, Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature (with North.One thousand. Wilson).

References [edit]

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. California: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 215. ISBN978-ane-60606-083-4.

- ^ Goh, M.; Schroeder, C., eds. (2018). The Brill Dictionary of Aboriginal Greek. Brill (Leiden). p. 1527 (col. three). ISBN978-90-04-19318-5.

- ^ Metzger, B. Yard.; Ehrman, B. D., eds. (2005). The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. Oxford Academy Press. p. 20. ISBN978-019-516122-9.

- ^ "In the Sinai, a global team is revolutionizing the preservation of aboriginal manuscripts". Washington Mail Magazine. September 8, 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-07 .

- ^ The Institutes of Gaius, ed Westward.Yard. Gordon and O.F. Robinson, 1988

- ^ Sadeghi, Behnam; Goudarzi, Mohsen (March 2012). "Ṣan'ā' 1 and the Origins of the Qur'ān" (PDF). Der Islam. 87 (1–two): 1–129. doi:10.1515/islam-2011-0025. S2CID 164120434. Retrieved 2012-03-26 .

External links [edit]

- OPIB Virtual Renaissance Network activities in digitizing European palimpsests

- Cursory annotation on economical and cultural considerations in production of palimpsests

- PBS NOVA: "The Archimedes Palimpsest" Click on "What is a Palimpsest?"

- Rinascimento virtuale a projection for the census, description, study and digital reproduction of Greek palimpsests

- Ángel Escobar, El palimpsesto grecolatino como fenómeno librario y textual, Zaragoza 2006

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palimpsest

0 Response to "Letters Made Out of Objects Layered Over and Over Again"

Post a Comment